I’ve been so captivated by computers, yet I’ve never really stopped to learn how they work. This year I’m aiming to solve this mystery by completing the Nand2Tetris course. I recently finished the first part of the course, which consists of 6 projects.

Along the way, I built a 16-bit computer capable of performing integer arithmetic and managing input/output (I/O) operations from a keyboard and screen. I also wrote an assembler to convert programs written in a basic assembly language into binary code for this computer to run. In this post, I’ll share my favorite insights on computing from the course.

Contents#

- Everything can be Built Using NAND Gates

- A Clever Binary Representation for Signed Integers

- What Clock Speeds Represent

- How Computers Interface with I/O Devices

- Basic Structure of a Modern Computer

- The Purpose of Assembly Languages

- Conclusion

Everything can be Built Using NAND Gates#

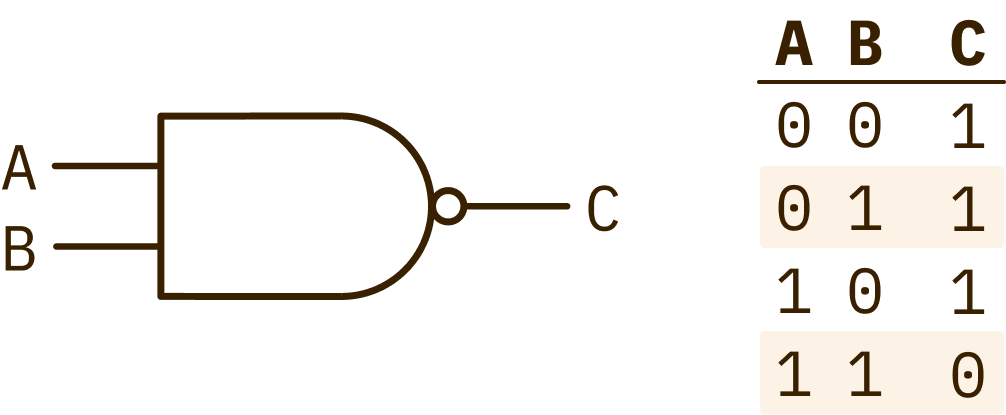

It was surprising to learn that all hardware in a computer can be built using only NAND gates. The first two projects made this clear.

Here, I started by building basic logic gates and leveraging these to construct more complex devices, such as an Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU), that are required for binary arithmetic operations.

This understanding helped me grasp how computers interpret binary programs. Binary instructions can serve as control parameters for hardware devices. For instance, the ALU I built has 6 bits that dictate which arithmetic operations it should perform. These control bits are just inputs to the NAND logic gates that comprise the ALU.

A Clever Binary Representation for Signed Integers#

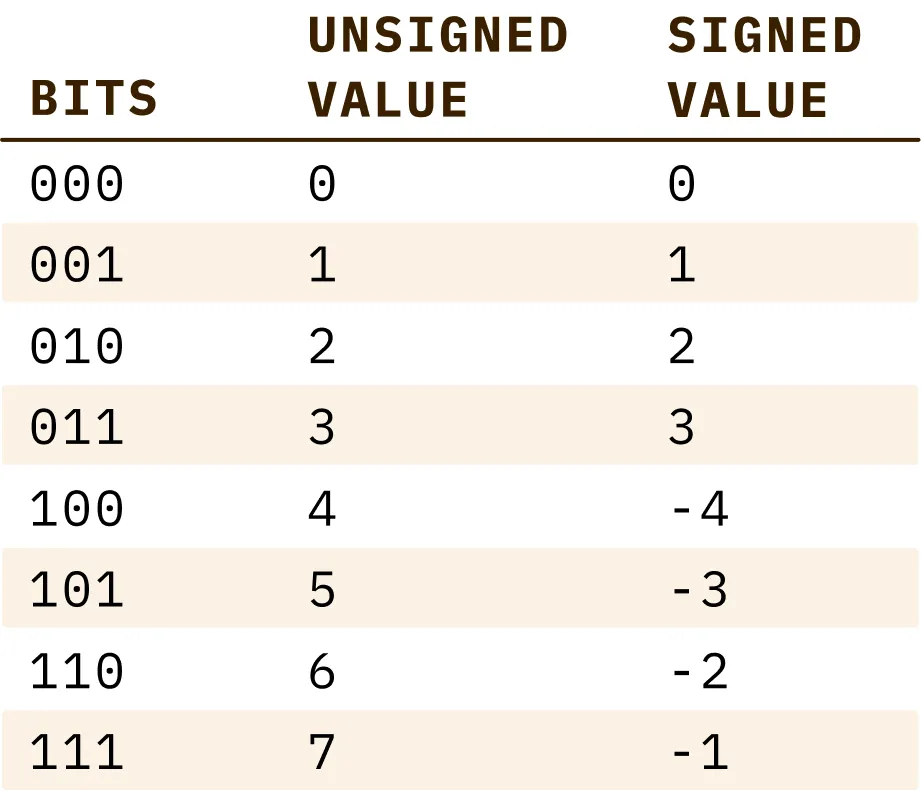

The method known as the Two’s Complement provides a convenient way to represent signed integers in binary. In an -bit system, this method can represent numbers in the range of to .

The Two’s Complement represents positive numbers in their standard binary representations. Negative numbers are obtained by taking their positive equivalents, flipping all the bits, and adding 1. For instance, the number 2 in a 4-bit system is represented as 0010, while -2 is represented as 1110. The nice thing about this is that subtraction gets handled as a special case of addition.

For instance, 2-2 can be computed by representing this as 2 + (-2) by calculating the result of 0010 + 1110). Here, the overflow would be ignored, yielding the correct answer 0000.

It’s also easy to tell apart positive numbers from negative numbers, as the most significant bit (MSB) serves as a sign bit. For positive numbers, the MSB is 0, whereas the MSB is 1 for negative numbers.

What Clock Speeds Represent#

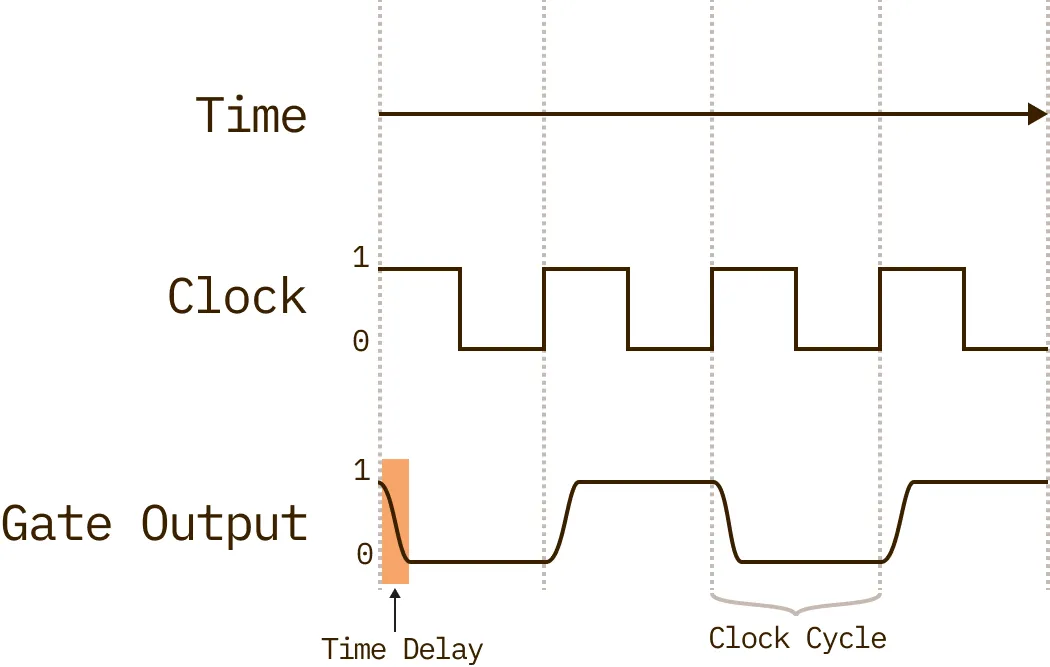

Clocks speeds measure how fast computers can perform computations. When a computer chip executes a task, the binary outputs of that execution don’t become instantaneously available to other hardware components that are awaiting those results.

It takes time for the results of computations to propagate to other chips. Here, time is measured in terms of indivisible units known as clock cycles. The clock speed determines the clock cycle duration.

Hardware designers must ensure the clock cycle duration exceeds the maximum time required for computational results to propagate between chips and for executing the most time-consuming operations within a chip. If this isn’t the case, a computer’s hardware components won’t work in sync.

Take, for example, the program consisting of the following steps:

- Calculate

1 + 2 - Store this result in memory

- Take the result of the previous computation and add 3 to it

One area where clock speed is important is the second step, where the results of the calculation 1 + 2 are stored in memory.

If the clock speed is too fast, the computer will not have enough time to store this into memory by the time it executes the third step. Thus, clock speeds are constrained by the physical limitations of hardware.

How Computers Interface with I/O Devices#

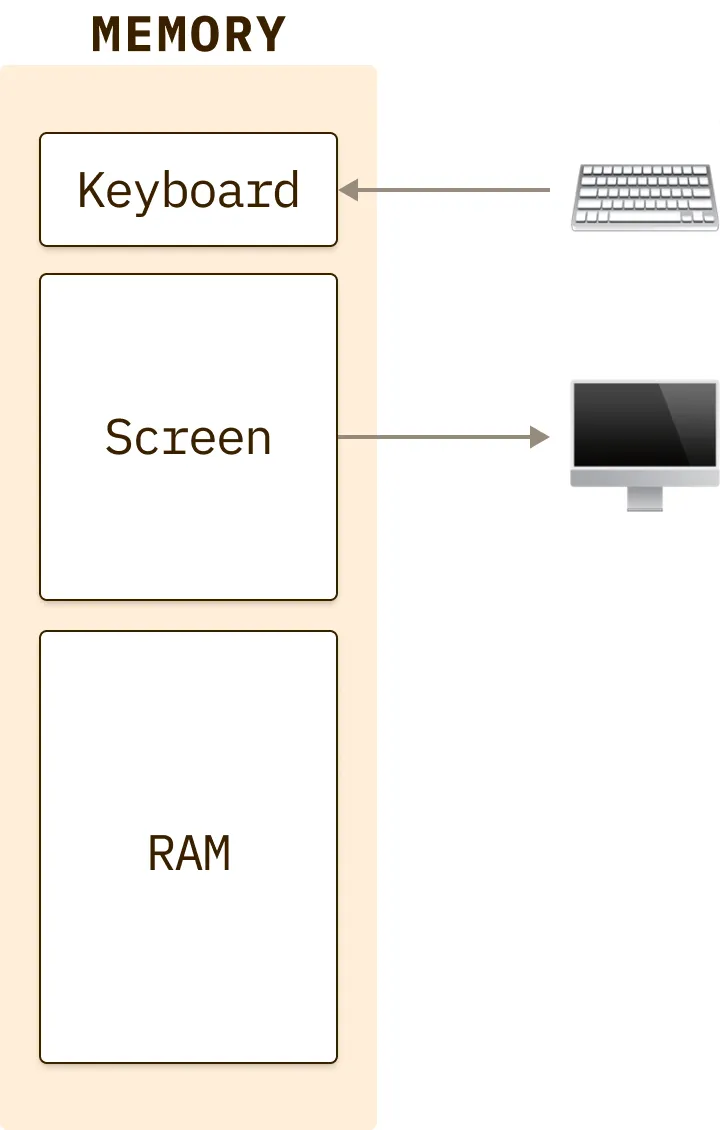

In a computer, external devices are mapped onto chunks of memory. Computers then interface with these devices by reading and writing to these memory maps.

For instance, a monitor’s pixels get mapped onto a series of memory registers, which store information regarding each pixel’s state. A computer can render graphics on the screen by writing, one pixel at a time, to the screen’s memory map.

Similarly, keyboards get mapped to a register that stores information regarding the most recently typed character. When a user types a key, the computer’s operating system reads the keyboard’s corresponding memory register, fetches the bitmap image associated with the typed character, and writes to the screen’s memory map to display the character.

I now understand why it’s important to have drivers installed when connecting new devices. Without these, a computer will have no instruction manual on how to interface with the device’s memory maps to operate them.

Basic Structure of a Modern Computer#

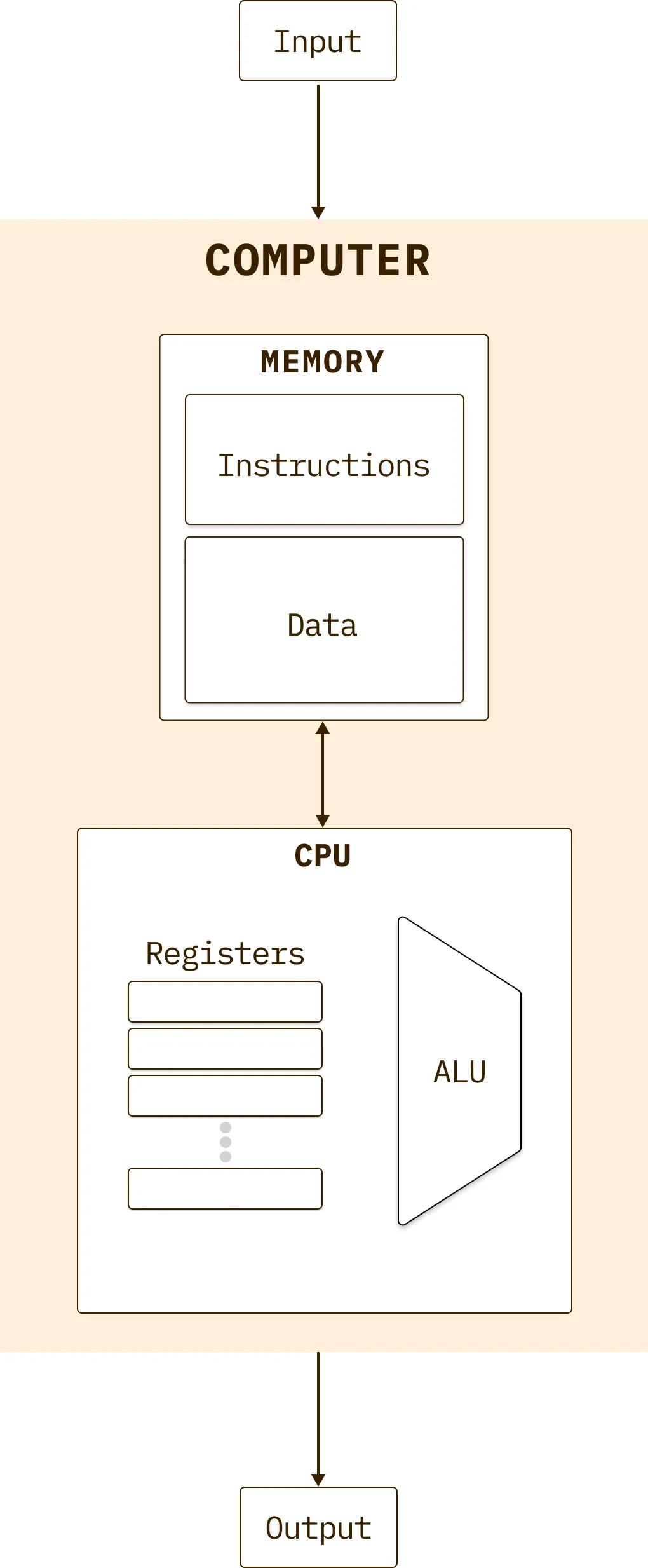

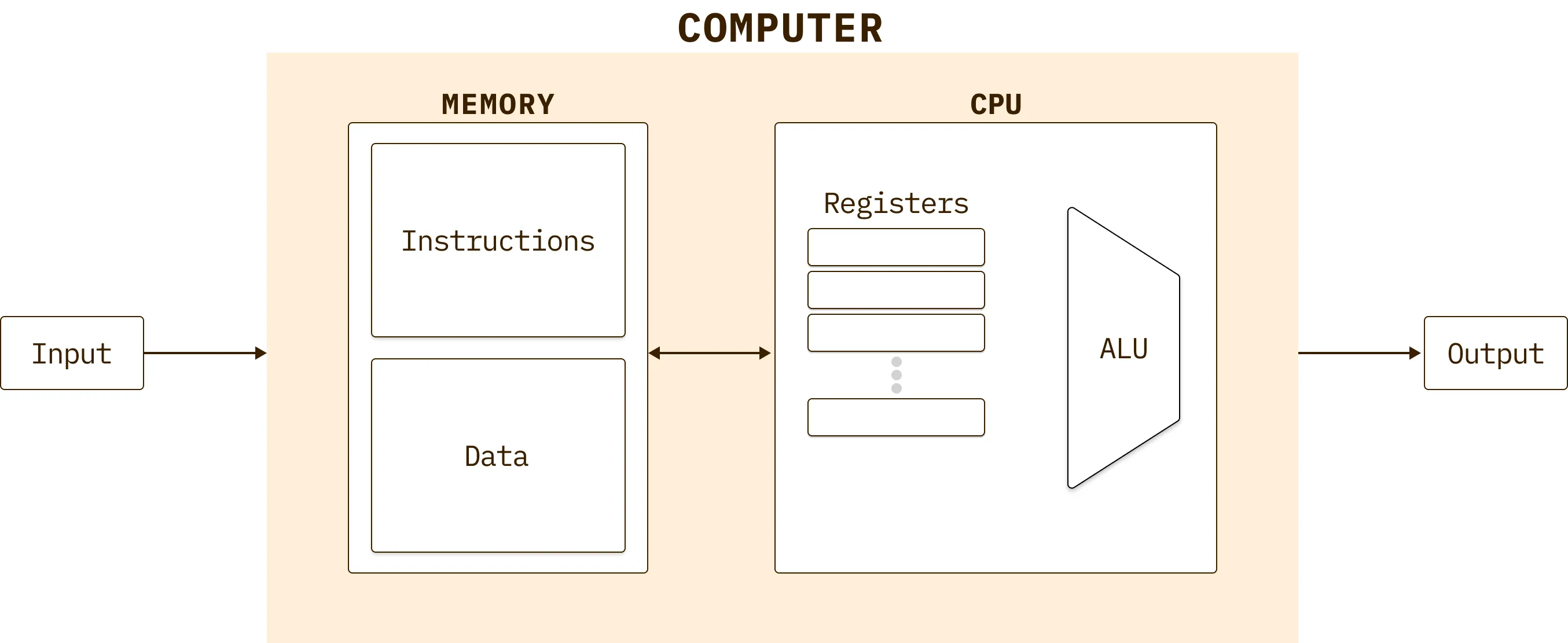

Most modern computers are based on the von Neumann architecture, created by John von Neumann. This consists of a central processing unit (CPU) that interfaces with a memory device, processes data from input devices (such as keyboards), and generates outputs to output devices (such as screens).

In this scheme, the memory’s hardware includes a series of addressable registers, of a fixed size, that each have a unique address. Access to the data contained in these registers occurs within the same clock cycle, regardless of the memory’s size and location.

Furthermore, the CPU can read and write two types of memory. These include data memory, which stores programming artifacts like variables, objects, and arrays, as well as instruction memory, which stores instructions for programs.

The CPU comprises the heart of the von Neumann architecture. It operates on a fetch-execute cycle, where the CPU fetches an instruction from memory, executes it, and repeats this procedure for the next instruction. CPUs leverage onboard memory registers to store interim values, addresses, and instructions that they need to perform computations. Loading these data directly from external memory is much slower and will bottleneck the CPU’s performance.

The Purpose of Assembly Languages#

Computers can only run programs written in binary code. But, most people can’t efficiently read and write programs in binary.

Assembly languages bridge that gap. They provide a means to write human-readable programs that can be directly translated into binary. There’s a direct 1:1 correspondence between a line of assembly code to a binary instruction.

Furthermore, assembly languages are each tailored to a target hardware platform. This is because computer architectures, such as ARM and x86, each have different specifications for interpreting binary instructions. Here, it’s clear to me now why you can’t generate a binary that runs on any architecture.

Conclusion#

Completing the exercises in Nand2Tetris Part 1 helped me understand the fundamental concepts of modern computers. These range from the basic logic gates that serve as building blocks all the way to the low-level assembly languages used to program the hardware. Now, computers are not as mysterious to me as they were when I first started the course.

But, the only mystery left for me to resolve is how software, such as operating systems and compilers, fits in the bigger picture of computing. I look forward to learning more about these concepts in the second part of the course.